Published in the 2016 September issue of the Asian Art Newspaper.

In the domain of ever-changing art world preoccupations, Dansaekhwa is the new black. The 20th century Korean movement, with its neutral monochrome and strong affinity for abstraction, has recently garnered a universal appeal. This appeal has found it’s calling -manifested through worldwide exhibitions and new market records. The recent exhibitions at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles; Alexander Gray Associates, New York; White Cube and Lisson Gallery, London and Kukje Gallery, Seoul are only a few showcases that bear testimony to this fact. The Dansaekhwa presentation at the 2015 Venice Biennale further reinforced the stronghold that this phenomenon has garnered in the international art sphere.

Dansaekhwa: More than a movement?

Dansaekhwa literally translates to monochrome. Indeed, it does just that. Eschewing vibrant kaleidoscopic colours, in favour of monochromatic tonality, the Dansaekhwa paintings are both reflective and stimulating. Art critic Lee Yil coined the term in 1980 to describe these neutral-hued abstract paintings. The movement came about in the 1970s in South Korea, in the backdrop of the political and social unrest following the Korean War.

While it can be attributed to ushering in modernism into South Korea, it is very hard to compare it to Western models of Modernism. For one, this movement was spearheaded by the drive to return to nature, by eliminating the pictorial subject. According to Kim Tae-Ho, one of the major Dansaekhwa proponents:

“Dansaekhwa is in respect of nature and purely backgrounded by oriental abstraction with spirit. Thus, it is meditation through repetition with no purpose, and a ‘fruit of artistic process of practicing’. Dansaekhwa is also a way of self-training with his/her own creative language to include internal spirit.”

Though this school of painting was a retort to western Modernism, it was also aided by a refutation of traditional style as exemplified by the National Exhibition. Despite this blatant rejection, it was firmly rooted in the muted palette of the Asian ink technique. The movement sought to reconnect and reinforce Korean identity, incorporating traditions from the Chosun dynasty and Eastern religions.

Critics would argue whether Dansaekhwa is in fact an art movement at all. Unlike an artistic movement, it is deprived of a manifesto that binds the artist’s intention. Perhaps what tied their early practice together in the post war clime was the existential perspective, characterized by the use of material forms and somber tones. Journeying along, this focus became ideologically diffused. It was this diluted context that proved to be the backbone of Dansaekhwa.

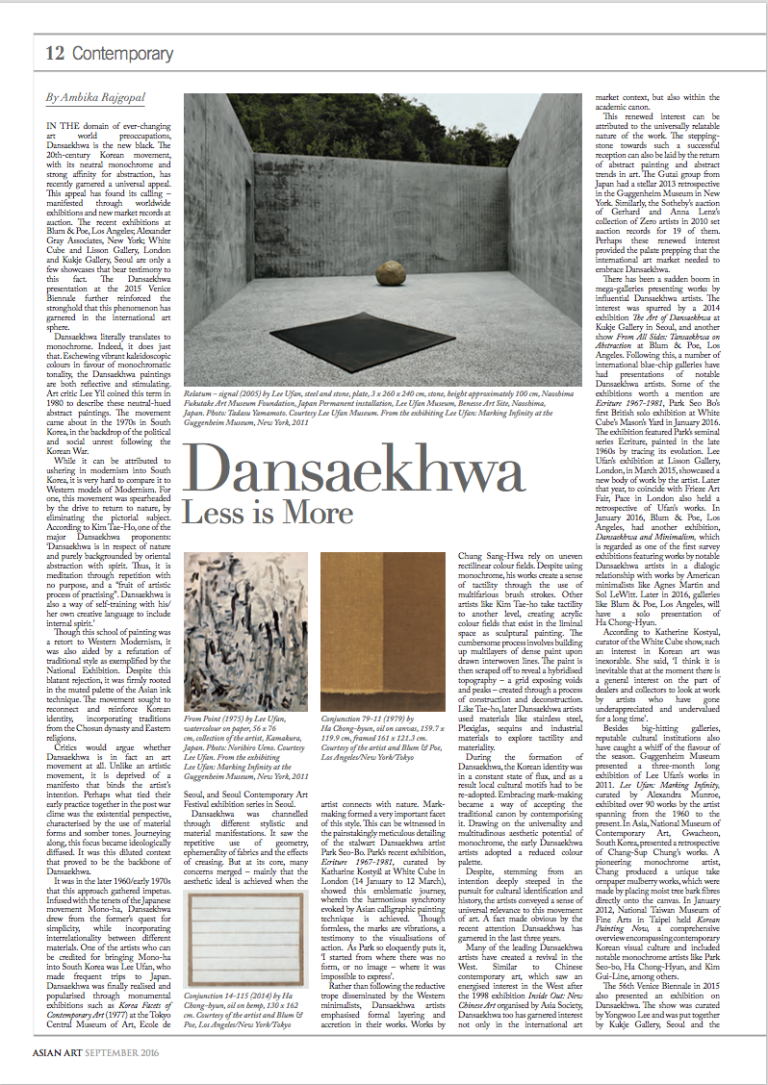

It was in the later 1960s- early 1970s that this approach gathered impetus. Infused with the tenets of the Japanese movement Mono-ha, Dansaekhwa drew from the former’s quest for simplicity, while incorporating interrelationality between different materials. One of the artists who can be credited for bringing Mono-ha into South Korea was Lee Ufan, who made frequent trips to Japan. Dansaekhwa was finally realized and popularized through monumental exhibitions such as Korea Facets of Contemporary Art (1977) at the Tokyo Central Museum of Art, École de Seoul and Seoul Contemporary Art Festival exhibition series in Seoul.

Dansaekhwa was channelized through different stylistic and material manifestations. It saw the repetitive use of geometry, ephemerality of fabrics and the effects of creasing. But at its core, many concerns merged – mainly that the aesthetic ideal is achieved when the artist connects with nature. Mark-making formed a very important facet of this style. This can be witnessed in the painstakingly meticulous detailing of the stalwart Dansaekhwa artist Park Seo-Bo. Park’s recent exhibition, Ecriture (描法) 1967-1981: Curated by Katharine Kostyál at White Cube in London, showed this emblematic journey, wherein the harmonious synchrony evoked by Asian calligraphic painting technique is achieved. Though formless, the marks are vibrations, a testimony to the visualisations of action. As Park so eloquently puts it, “I started from where there was no form, or no image – where it was impossible to express.”[1]

Rather than following the reductive trope disseminated by the western minimalists, Dansaekhwa artists emphasized formal layering and accretion in their works. Works by Chung Sang-Hwa rely on uneven rectilinear colour fields. Despite using monochrome, his works create a sense of tactility through the use of multifarious brush strokes. Other artists like Kim Tae-ho take tactility to another level, creating acrylic colour fields that exist in the liminal space as sculptural painting. The cumbersome process involves building up multilayers of dense paint upon drawn interwoven lines. The paint is then scraped off to reveal a hybridized topography – a grid exposing voids and peaks – created through a process of construction and deconstruction. Like Tae-ho, later Dansaekhwa artists used materials like stainless steel, Plexiglas, sequins and industrial materials to explore tactility and materiality.

During the formation of Dansaekhwa, the Korean identity was in a constant state of flux, and as a result local cultural motifs had to be re-adopted. Embracing mark-making became a way of accepting the traditional canon by contemporizing it. Drawing on the universality and multitudinous aesthetic potential of monochrome, the early Dansaekhwa artists adopted a reduced colour palette.

Despite, stemming from an intention deeply steeped in the pursuit for cultural identification and history, the artists conveyed a sense of universal relevance to this movement of art. A fact made obvious by the recent attention Dansaekhwa has garnered in the last three years.

The world’s Dansaekhwa moment

Many of the leading Dansaekhwa artists have created a revival in the West. Similar to Chinese contemporary art, which saw an energized interest in the West after the 1998 exhibition Inside Out: New Chinese Art organized by Asia Society, Dansaekhwa too has garnered interest not only in the international art market context, but also within the academic canon.

This renewed interest can be attributed to the universally relatable nature of the work. The stepping-stone towards such a successful reception can also be laid by the return of abstract painting and abstract trends in art. The Gutai group from Japan had a stellar 2013 retrospective in the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Similarly, the Sotheby’s auction of Gerhard and Anna Lenz’s collection of Zero artists in 2010 set auction records for 19 of them. Perhaps these renewed interest provided the palate prepping that the international art market needed to embrace Dansaekhwa.

There has been a sudden boom in mega-galleries presenting works by influential Dansaekhwa artists. The interest was spurred by a 2014 exhibition The Art of Dansaekhwa at Kukje Gallery in Seoul, and another show From All Sides: Tansaekhwa on Abstraction at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles. Following this, a number of international blue-chip galleries have had presentations of notable Dansaekhwa artists. Some of the exhibitions worth a mention are Ecriture 1967-1981, Park Seo Bo’s first British solo exhibition at White Cube’s Mason’s Yard in January 2016. The exhibition featured Park’s seminal series Ecriture, painted in the late 1960s by tracing its evolution. Lee Ufan’s exhibition at Lisson Gallery, London in March 2015, showcased a new body of work by the artist. Later that year, to coincide with Frieze art fair, Pace, London also held a retrospective of Ufan’s works. In January 2016, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles had another exhibition Dansaekhwa and Minimalism, which is regarded as one of the first survey exhibitions featuring works by notable Dansaekhwa artists in a dialogic relationship with works by American minimalists like Agnes Martin and Sol LeWitt. Later in 2016, galleries like Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, will have a solo presentation of Ha Chong-Hyun.

According to Katherine Kostyal, curator of the White Cube show, such an interest in Korean art was inexorable. She said, “I think it’s inevitable that at the moment there is a general interest on the part of dealers and collectors to look at work by artists who have gone underappreciated and undervalued for a long time”.[2]

Besides big-hitter galleries, reputable cultural institutions also have caught a whiff of the flavor of the season. Guggenheim Museum presented a three month long exhibition of Lee Ufan’s works. Lee Ufan: Marking Infinity, curated by Alexandra Munroe, exhibited over 90 works by the artist spanning from the 1960 to the present. In Asia, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, South Korea, presented a retrospective of Chang-Sup Chung’s works. A pioneering monochrome artist, Chang produced unique tak or paper mulberry works, which were made by placing moist tree bark fibers directly onto the canvas. In January 2012, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taipei held Korean Painting Now, a comprehensive overview encompassing contemporary Korean visual culture and included notable Monochrome artists like Park Seo-bo, Ha Chong-Hyun and Kim Gui-Line, among others.

The 56th Venice Biennale in 2015 also presented an exhibition on Dansaekhwa. The show was curated by Yongwoo Lee and was put together by Kukje Gallery, Seoul and Tina Kim Gallery, New York. The purpose of the exhibition was to provide a wide-ranging outline of the Korean monochrome movement through the works of some seminal artists, thereby giving the conceptual framework within which Dansaekhwa operated. Taking place across three floors of the Palazzo Contarini-Polignac, the exhibition featured all the likely suspects – artists like Chung Sang-Hwa, Kwon Young-Woo, Lee Ufan, Chung Chang-Sup, Park Seo-Bo, among others. Via the works of these artists, who all worked at different points in time, the social milieu that provided the contextual backdrop for Dansaekhwa, could be painted. Furthermore, the political and social climate had a strong bearing on how the movement developed and was subsequently received by the public.

This inclusion of the Dansaekhwa in the Biennale had a strong repercussion in the art world. The movement was finally recognized as having not just art market credibility, but also cultural and academic integrity. Picking up on this, Greenfell Press published a 323-page volume on Dansaekhwa, the first English book of its kind. Starting with an introduction written by Yong-woo, the Director of the Shanghai Himalayas Museum and former president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, the book also featured a number of notable scholars such as Alexandra Munroe; Melissa Chiu, director of the Smithsonian’s Hirschhorn Museum; and Chong Do-ryun, chief curator of M+ Museum in Hong Kong, among others. This book has had a strong impact on the reception of Dansaekhwa in the English-speaking world, enabling access and a better understanding into this late 20th century Korean movement.

Following this academic interest in Dansaekhwa, major cultural institutions also realized its art historical importance. Museums like Museum of Modern Art and Guggenheim Museum, New York; British Museum, London; the Centre Pompidou, Paris; the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; and Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C. were quick to acquire works by artists like Kim Tae-Ho, Ha Chong-Hyun, Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo.

The success of Dansaekhwa was realized not just by the exhibition and acquisition history, but also by quantifiable auction figures. In 2015, both Christie’s and Sotheby’s organized a curated exhibition focusing on Dansaekhwa. While the former organized a selling exhibition featuring 60 works in New York and Hong Kong, the latter organized Avant Garde Asia: Lines of Korean Masters in Hong Kong to coincide with Art Basel.

Since 2014, many works by key Dansaekhwa artists have sold for more than $ 100,000 each at auction. Previously, only 4 works of art achieved this feat. Despite most of the sales taking place in Hong Kong, more than half of the bidders have been Western collectors and dealers. Auction records of notable Dansaekhwa artists like Chung Sang-Hwa, Kwon Young-Woo, Yun Hyong-Keun have all been broken in the last one year.

Many of the works have experienced a sudden surge in auction price. According to a key gallerist, primary prices for Dansaekhwa artists have augmented by up to 200% since 2014. One significant artist whose auction prices encapsulate this inflated demand is Park Seo-Bo. Park’s 1982 work Ecriture 3-82, sold in an auction in November 2013 for $56,750. In May 2015, it was resold for $631,972 – at more than a 91% increase in price. Similarly another work from the Ecriture series sold in December 2014 for $55,432; a comparable work sold in November 2015 for $838,633, indicating a 93% increase in price.

Although the international auction market has seen more escalated prices, this heightened price indicates a renewed interest in non-Western artists. Only a couple of years ago, these artists would be found only in regional auctions. After the interest in Gutai movement, it is Dansaekhwa’s turn to reign over the international art market.

[1] Park, Seo-bo. Artist statement of solo exhibition at Tokyo Gallery, June 1973.

[2] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-korean-minimalism-is-the-next-big-art-market-trend-here-s-why